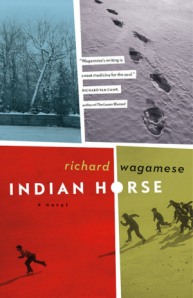

Indian Horse, by Richard Wagamese, is written in sparse, straight-forward prose. It is the story of Saul Indian Horse, a thirty-something Ojibway man; Saul is in a treatment center — in his case, for alcohol abuse — and he is writing the story of his life as therapy.

His story is brutally sad; he was separated from his family, put in a residential school, and as a child could only find solace while playing hockey, a game that he seems born to play. Saul has a memory buried in the dark recesses of his psyche and it takes him decades to unlock the source of his inner anger: it is more than the prejudice he encounters from the Zhaunagush, the white man, and it is even more than the losses of family members that he has suffered.

His story is brutally sad; he was separated from his family, put in a residential school, and as a child could only find solace while playing hockey, a game that he seems born to play. Saul has a memory buried in the dark recesses of his psyche and it takes him decades to unlock the source of his inner anger: it is more than the prejudice he encounters from the Zhaunagush, the white man, and it is even more than the losses of family members that he has suffered.

The novel includes some mystic sections, some brutal acts (particularly during Saul’s time in the residential school) and several examples of the typical prejudicial behaviour that First Nations peoples are/were exposed to in Canada, a country that assumes a false pride for its acceptance of all cultures and races.

I liked the novel, and I particularly enjoyed the sections that explore the spirituality and atmosphere of the First Nations’ connection to the natural environment. The author writes with a sincere clarity, and I found the sections that were set in the wilderness to be filled with a simple, poignant quality:

.

“One day the clouds hung low and light rain freckled the slate-grey water that peeled across our bow. The pellets of rain were warm and Benjamin and I caught them on our tongues as our grandmother laughed behind us. Our canoes skimmed along and as I watched the shoreline it seemed the land itself was in motion. The rocks lay lodged like hymns in the breast of it, and the trees bent upward in praise like crooked fingers. It was glorious. Ben felt it too. He looked at me with tears in his eyes, and I held his look for a long time, drinking in the face of my brother.” [p. 18]

.

I wish there were more sections set in the wilderness, but this novel delivers a message that takes the reader in a different direction; it is a melancholy reminder that we have a long way to go before our society can be termed enlightened, and we all require spiritual guidance and the helping hand of friends and family.

.

.

.